Bollywood Dreams and Bazaar Scenes

The Gerrard India Bazaar, also known as “Little India”, was a vital community space for Toronto’s first Indian and Pakistani immigrants. Now over 50 years old, the Bazaar remains a vibrant part of the city, serving both the South Asian community and Canadians of many other backgrounds.

Contents

This story was researched and written by Emerging Historian Sarah Takhar (2023) and made possible by the generous support of our Tours Program Presenting Sponsor, TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment, Emerging Historian Champion Andrew and Sharon Himel and Family, and Alexandria Pike.

Last updated: June 27, 2024

We’d love to hear your feedback. Contact us.

Becoming Little India

The first economic and community hub for South Asian immigrants in Toronto originated in the 1970s.

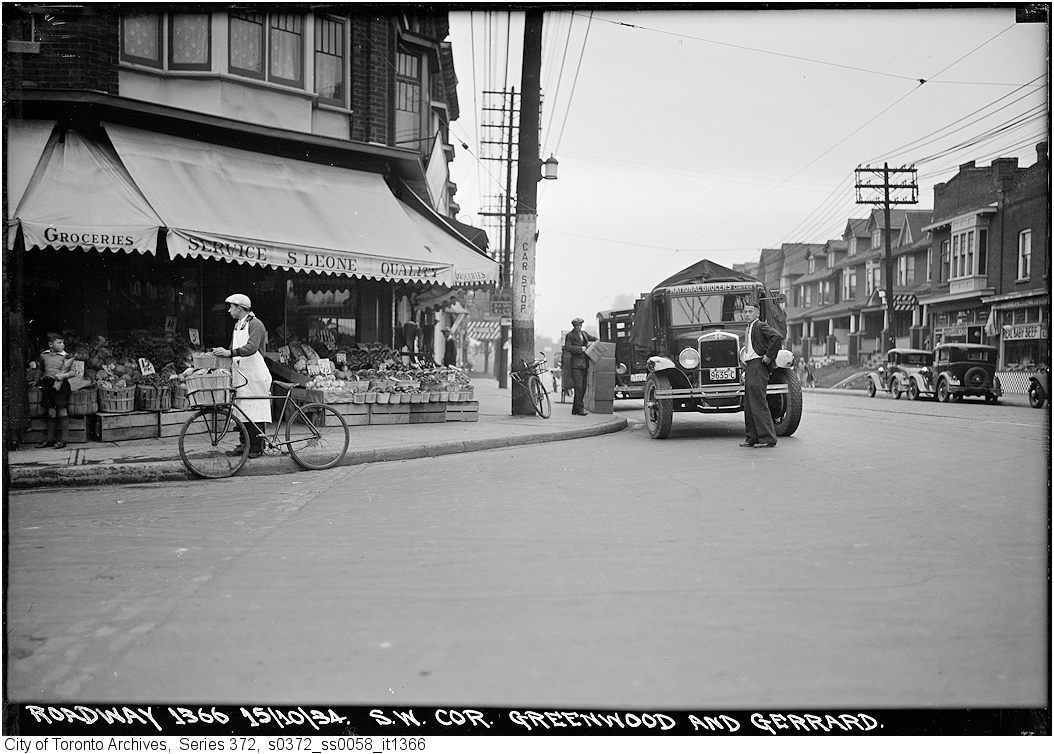

Located along Gerrard Street East, from approximately Greenwood Avenue to Coxwell Avenue, sits the Gerrard India Bazaar. Also known as Toronto’s “Little India”, this area has been attracting visitors for over five decades with unique businesses and cultural events. Recognized around the world as a hub for Toronto’s South Asian community, the Indian newspaper India Today compared the Bazaar to London’s Southall, England’s own “Little India” boasting the largest Punjabi community outside of India.

To understand the origins of this community hub, we should look at the broader history of this Toronto neighbourhood. Throughout much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the area was largely home to English, Irish, and Scottish households, many of whom worked in the neighbourhood’s brickyards or industrial businesses, such as the Wrigley’s Chewing Gum factory on nearby Carlaw Avenue.

By the mid-20th century, the neighbourhood began to see an increase of Italian and Greek residents as Canada’s post-World War II job market attracted large numbers of Southern European immigrants. The 1960s, however, brought a decline to many businesses along Gerrard. Many of the area’s residents began moving to Toronto suburbs for larger homes and affordable land. Around the same time, Chinese and Indian immigrants began moving to the area, interested in the low cost of Gerrard Street East’s real estate.

Southwest corner of Gerrard Street East and Greenwood Avenue prior to the development of the Gerrard India Bazaar. October 15, 1934. Courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

South Asian Immigration

As Toronto’s South Asian community grew, the Gerrard Street East became an important economic hub.

The earliest recorded settlers to Canada from India arrived in the early 20th century. Like many other newcomer communities, South Asian newcomers faced Canada’s strict quota system, which only allowed 150 Indian, 100 Pakistani, and 50 Ceylonese immigrants per year to enter the country. This system ended in 1961, replaced by the 1967 Immigration Act that introduced a points-based immigration system. The new system emphasized a newcomer’s educational background or employment skills rather than country of origin, opening the doors to migrants of many backgrounds in South Asia to enter Canada. This resulted in a large population increase of South Asians in multiple regions of Canada, including Toronto.

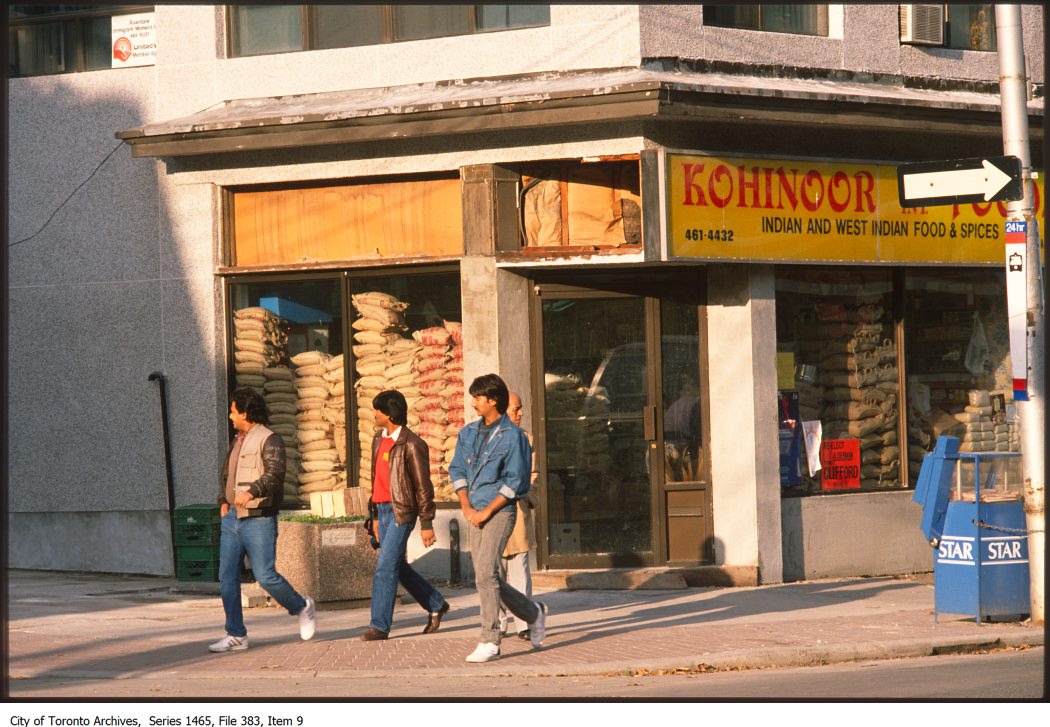

Despite the growth of Toronto’s South Asian community, Gerrard Street East never became a residential centre for the city’s South Asian residents, unlike other Toronto cultural districts such as Chinatown. Instead, the district developed into an economic hub for the community, with a wide variety of businesses featuring South Asian food, clothing, or household goods. This economic, rather than residential, focus is reflected in the area’s Business Improvement Area (BIA) name: the Gerrard India Bazaar.

Visitors to Little India walking past Kohinoor Foods, circa 1978-1988. Courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

The Theatre That Started It All

The Naaz Theatre drew crowds to Gerrard Street East.

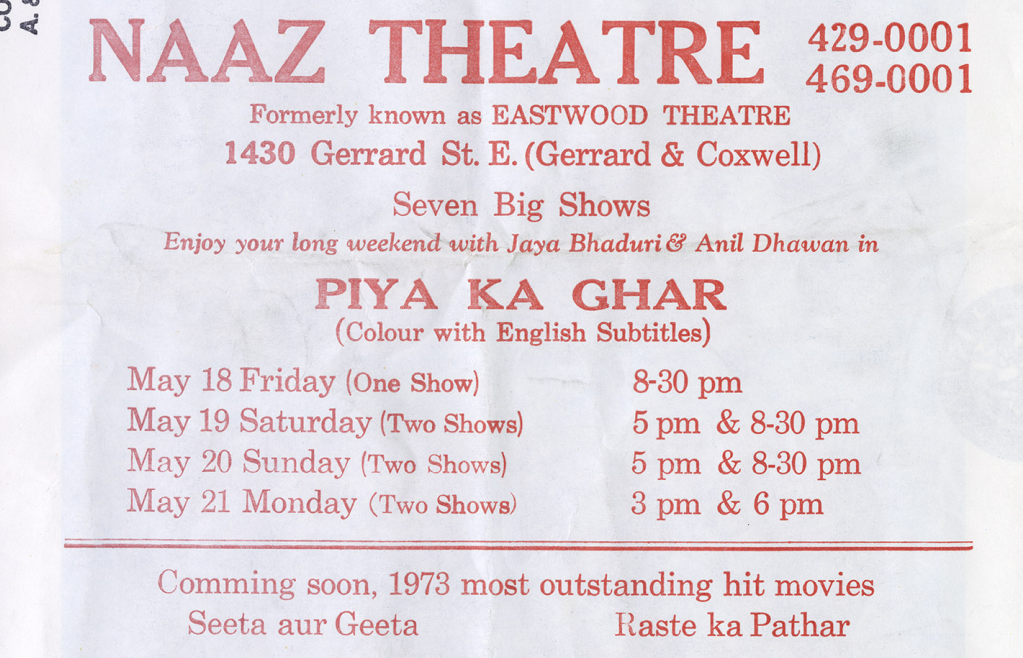

Gian Naaz immigrated from India to Toronto with his family in 1968. Not long after his move to Canada, he began to host screenings of Indian (or Bollywood) films in rented school halls. In 1972, aware of his fellow immigrants’ interest in Indian cinema, Naaz began renting the abandoned Eastwood theatre at 1430 Gerrard Street East. The popularity and demand for Indian films enabled Naaz to purchase the theatre in 1974; he renamed it the Naaz Theatre and began holding regular showings of Bollywood films.

In these early days, the theatre offered three showings on Saturdays, with audiences almost filling the space to capacity. Tickets were $3.50, and food such as samosa or chana masala were available from the theatre’s snack bar. With the popularity of the theatre, other South Asian businesses began to open nearby, serving the South Asian clients who made their weekend pilgrimages to the area to enjoy a Bollywood film.

Once [the Naaz Theatre] started showing the movies, a restaurant opened up beside, a record store opened up beside; that is how the Gerrard India Bazaar was incepted, and slowly and slowly the business grew.

Inder Jandoo, Vice Chair of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Sonu Saree Palace, Interview, December 4, 2023.

Toronto’s Naaz Cinema, Gerrard Street East, circa1980. Image by Erin Combs. Courtesy of the Toronto Star Archives.

There used to be a big line up at that time for the theatre because there were limited seats and there were a lot of people who wanted to watch the movies… the line used to go close to a block long

Inder Jandoo, Vice Chair of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Sonu Saree Palace, Interview, December 4, 2023

The Magic of Bollywood

Indian cinema is more than escapism, it is culture and community.

It may seem surprising that the opening of a movie theatre led to the development of a thriving commercial district, but Indian cinema is very interwoven into Indian culture. The 1970s are known as the golden age of Indian cinema and birthed the term “Bollywood”, a combination of the words “Bombay“ and “Hollywood.”

Indian cinema has always stood out for its music, dancing, and deep connection to traditional Indian culture. For the Indian diaspora, the films were a way of going home for a few hours, showing familiar culture, places, and celebrities, like Amitabh Bachchan, on the big screen. For many Indian families in the 1970s, going to the theatre was a big event, a cultural phenomenon Naaz reproduced for South Asian immigrants.

The Naaz Theatre was also the first of its kind in North America, drawing visitors from both Canada and the United States. Neighbourhood business owners can recall visitors coming to the Bazaar from as far away as New Jersey or even Florida. The Naaz Theatre and the Bazaar provided a place where South Asians could speak their native language and find a sense of community within their new country.

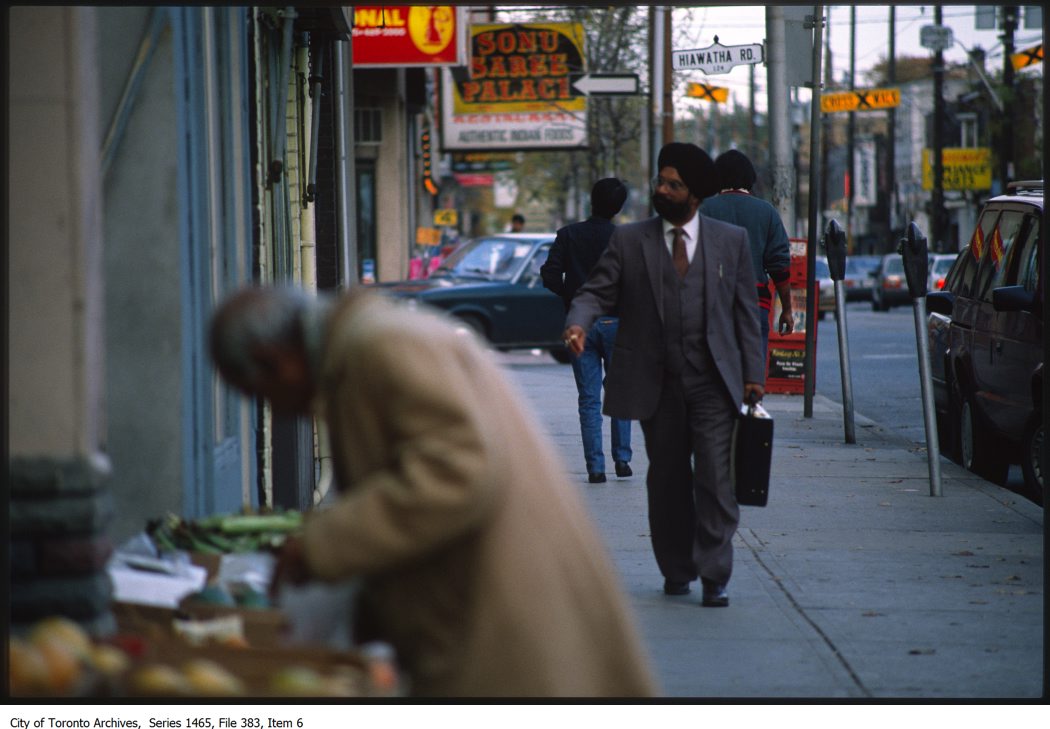

Contrary to the name “Little India”, the visitors and the businesses along Gerrard Street East were not exclusively Indian. People from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka gravitated to the area, as well as people from other communities of South Asian heritage, such as Ugandan Ismailis and Indo-Caribbeans.

Seeing a Bollywood movie means that you are sitting back home in a cinema, and you are watching that movie along with your friends…you’re laughing together, you’re crying together…It became a meeting joint, ‘ok alright I’ll see you on Friday at the 6 o’clock show and then we’ll have dinner together.’

Inder Jandoo, Vice Chair of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Sonu Saree Palace, December 4, 2023

Naaz Theatre advertisement for the showing of the Bollywood film Piya Ka Ghar, May, 1973. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library.

[Gerrard Street East] was a small market that was known around the world. We had a lot of American clients, American tourists that would come through.

Chandan Singh Inder Jandoo, Secretary of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Chandan Fashion, Interview, December 19, 2023

Visitors walking the street of the Gerrard India Bazaar circa 1976-1988. Courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

More or less at that time a trip to Gerrard India Bazaar was half a trip to India.

Inder Jandoo, Vice Chair of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Sonu Saree Palace, Interview, December 4, 2023

A Changing Bazaar

The closing of the Naaz Theatre in 1985 as well as the increased accessibility to international products has impacted the Bazaar.

The Naaz Theatre shut down in the 1980s, unable to compete with the new technology of VHS tapes: People could now watch movies within the comfort of their own homes. While the shutting of the theatre was a loss for the community, other businesses continued to operate in the area. Bollywood movies were now available to purchase on VHS tape and eventually DVDs in the same shops where visitors bought their groceries.

The 1990s brought along more changes for the Bazaar. For decades, Gerrard Street East was the only place in the Toronto area for South Asian food, fashion, jewellery, and cinema. Yet as the South Asian population began to grow in other areas, such as Scarborough, Mississauga, and Brampton, stores began to open there, where owners could be closer to the regular clientele with the added benefit of cheaper rent. The weekend pilgrimages to Gerrard Street East began to decline due to the convenience of South Asian stores in these new locations.

Today, the first generation of the Bazaar’s business owners are nearing retirement age and are looking to the next generation. However, many of their children are hesitant about are wanting to take over the family business, instead choosing to pursue alternative careers. The draw of the Bazaar for the younger generation has also changed. For example, many South Asian food products, like paneer cheese can be purchased in major supermarkets; South Asian clothing and accessories can be found in online shops, and international newspapers read online. Major movie theatre chains, such as Cineplex, frequently show popular Bollywood films and streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime offer a large catalogue of South Asian films.

Display at Chandan Fashion, 1439 Gerrard Street East, May 19, 2024. Image by Hammad Khalil.

Toronto is one of the most unique cities in the world, especially within Canada. We have so many deep pockets of culture, Little Italy, Little India, Little Portugal, Chinatown, Little Chinatown … In order for these little pockets to survive, they have to maintain their identity in some way, and this is a very tricky part.

Chandan Singh Inder Jandoo, Secretary of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Chandan Fashion, Interview, December 19, 2023

Gerrard Street Today

Adapting to a rapidly gentrifying city, Gerrard India Bazaar is reinventing itself for younger generations.

The Bazaar today is a changing space. Iconic shops such as Sonu Saree (opened c. 1979) and Chandan Fashion (opened c.1984) remain important fixtures in the community, while new stores from different cultures are also opening their doors. The new additions to Gerrard Street have brought a new diversity of shops and services, while drawing more foot traffic to the area. However, these newer stores are also representative of gentrification that has impacted the area for several decades.

Gentrification is something not all long-term business owners are mad about; many property owners have enjoyed significant return investment on buildings purchased for cheap only a few decades ago. For store owners, the changes to the area has brought new clientele and new interest in the Bazaar. Events such as the annual TD Festival of South Asia also have raised the profile of the Bazaar.

However, the question remains how to balance the culture and the unique fingerprint of “Little India” while also welcoming different businesses and clients into the area. Many business owners want Gerrard Street East to be a space that provides goods and services that aren’t exclusively South Asian, but they also don’t want to lose the identity and heritage the strip has created over the last fifty years. They want to provide a home-like space for South Asian newcomers to Toronto, but not to the exclusion of Canadians from everywhere else.

Gerrard Street business owners are looking to the next generation to open new shops with fresh and innovative ideas. This next generation, born and raised in Canada, could make their mark on the strip by providing services that blend South Asian and Canadian cultures. Shops that serve both area residents and South Asian clients by providing products with a little cultural twist may help to ensure the Bazaar lasts for the next fifty years.

2023 TD Festival of South Asia hosted in the Gerrard India Bazaar. Courtesy of the Gerrard India Bazaar BIA.

The next business that should open, it should be that 2.0 where it doesn’t have to be super traditional from India. It could be something a bit more modern, a bit more fusion. Let’s serve pizza for the neighbourhood, but let’s do it with a little tandoori chicken on there. Let’s do a clothing store that has [outfits] that have South Asian embroidery that you could wear to school, or a cheese shop that also carries Indian cheeses.

Chandan Singh Inder Jandoo, Secretary of Gerrard India Bazaar BIA and owner of Chandan Fashion, Interview, December 19, 2023.

Sponsors

Further Sources

TVO. “Little India: Village of Dreams“. Documentary and additional short videos on Little India published July 1, 2017.

Bateman, Chris. “What Little India used to look like in Toronto” blogTO. Article published November 30, 2014.

Bauder, Harald and Angelica Suorineni. “Toronto’s Little India: A Brief Neighbourhood History”. Toronto Metropolitan University. Online resource published June 30, 2010.

Hudson, Andrew. “Dinner and a movie the start of the Gerrard India Bazaar”. Beach Metro. Article published June 16, 2015.

Marlow, Iain. “Urban shift threatens to swallow Little India” The Globe and Mail. Article published December 21, 2012.

Yelaja, Prithi. “Little India: Six blocks, many stories” The Toronto Star. Article published August 25, 2007.