City Kids to Farm Hands: The Home Children

Between 1869 and 1948, over 100,000 children were brought to Canada from Britain through a juvenile emigration program. Dr. Barnardo arranged for many children to be sent to Toronto, where they were sent to work on farms or serve as domestic help. Known as the “Home Children”, their story is one of survival and perseverance.

Contents

This story was researched and written by Emerging Historian Georgina Warner (2023) and made possible by the generous support of our Tours Program Presenting Sponsor, TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment and Emerging Historian Champion Andrew and Sharon Himel and Family.

Last updated: May 23, 2024

We’d love to hear your feedback. Contact us.

Dr. Barnardo Arrives in Toronto

Dr. Barnardo’s name became synonymous with the child emigration scheme in both Britain and Canada.

In July 1884, Dr. Thomas John Barnardo arrived in Toronto with a mission: to find a headquarters for his new philanthropic organization. Barnardo, a man of humble beginnings, had been working for over ten years trying to alleviate child poverty in England. His organization, known as Barnardo’s, sought to bring impoverished British children from the streets of London, England to the fresh air of Canada.

While not the founder of the Canadian child emigration scheme, Barnardo’s organization became the largest sender of British children, responsible for an estimated 30,000 children arriving in Canada between the 1880s and 1940s. Although widely supported at the time, the program was eventually surrounded by controversy.

Halfpenny Dinners for Poor Children. East London, England. March 26, 1870. Illustration by The Illustrated London News. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

Victorian Britain & Aid for Children

The origins of the Home Children, and the child migration scheme, date to the 1760s when industrialization was changing British society.

Throughout the 1800s, Britain was facing an urban crisis. The effects of the Industrial Revolution (circa 1760-1840) had caused people to flock from the countryside to the city. This migration had contributed to both a rise in unemployment and a housing shortage within many British cities.

The 1832 British Royal Commission on the Poor Law and the Unemployed attempted to tackle the situation, resulting in the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. The Commission’s solution to pauperism was to force people to work their way out of poverty. Those who were able-bodied were only able to access assistance in workhouses and similar institutions.

In addition to government policies, social reformers and philanthropists, such as Barnardo, founded charities to help the poor. Although the crisis affected British citizens of all ages, several programs of the time focused on helping Britain’s impoverished urban children. Aid came in the form of shelters for adults, along with schools and homes for children. Reformers took an interest in farm schools and created rural ‘Cottage Homes’ where children could live and learn far away from the dangers of the cities. Yet, these organizations could not keep up with the number of those in need.

As early as 1825, a program to emigrate impoverished British children to Canada as farmhands was suggested to aid in Canada’s labour shortage, although the program did not take off until the 1870s. While other British colonies also received children, such as Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand, Canada was the preferred destination.

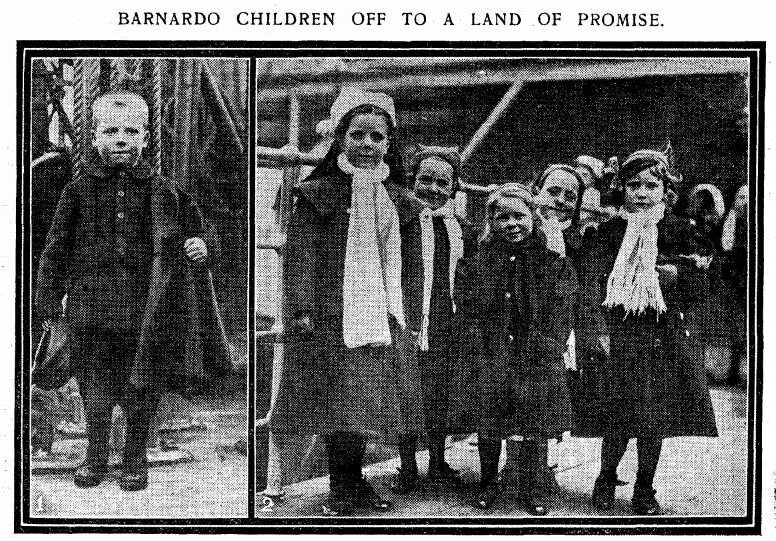

A group of Barnardo’s children going to Canada. Surrey, England. September 20, 1912. Image by Daily Mirror. Courtesy of Canadian British Home Children.

Canada is our nearest colony; it possesses an admirable climate; the journey thither is short and inexpensive; above all, Canada wants settlers, and can absorb hundreds and thousands of boys and girls for a long future.

Thomas John Barnardo, “Something attempted, something done!”, 1898.

Coming to Canada

The Home Children were distributed throughout the country, but Ontario became a particularly popular location.

By the late 19th century, hundreds of British children had been sent to Canadian “placements” through juvenile migration schemes, in which they would receive room and board in exchange for work. In the British imagination, Canada was often seen as a pious land of plenty, where children would benefit from fresh air and rural labour.

“Home children” were so known as they travelled from an emigration agency’s home for children in Britain to a receiving home in Canada. Receiving homes were set up by various philanthropic organizations all over the country, including Quebec, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia. Other philanthropists, such as Maria Rye and Annie MacPherson, had their hubs in Ontario, such as in Niagara-on-the-Lake or Belleville.

Initially, Barnardo used other charitable agencies to take children from his home systems in Britain, travel with them overseas, and send them onwards to farms or home sites throughout Canada. With the growing success of the program, Barnardo decided to open his own receiving home. His first home opened on Front Street in Toronto in the early 1880s, followed by a home in Peterborough. Althought the home on Front Street soon closed in favour of the Peterborough location, with the constant stream of children coming to Canada, Barnardo realized that an official headquarters needed to be established.

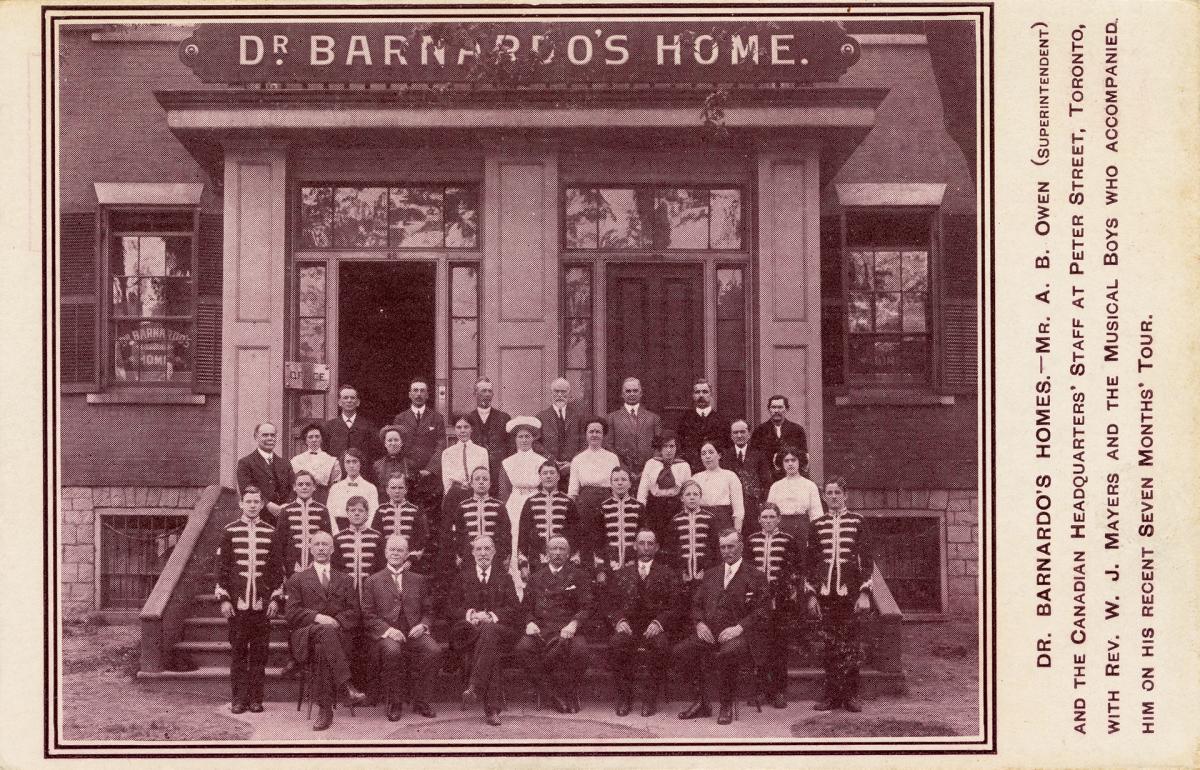

Between 1887 and 1945, Toronto served as the hub for Barnardo’s work in Canada. Over this period, Barnardo’s organization used three locations to receive and distribute children: 214 Farley Avenue (1887-1908), 50-52 Peter Street (1909-1922), and 538 Jarvis Street (1922-1945). Barnardo also opened a home for girls who became pregnant during their placements, located at 150-152 Bathurst Street, later moving into the vacated Farley Avenue headquarters.

Barnardo’s headquarters at 538 Jarvis Street. Toronto, Ontario. January 7, 1922. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

The headquarters in Farley Avenue [was] established in 1888, but in the meantime a small home had been opened near the Union Station. The growth of the emigration to Canada made a larger building an absolute necessity.

The Toronto World, September 21, 1905.

Off to Work

Challenging rural and domestic work coupled with demanding employers made the transition to Canadian life tough for many of these city children turned farm hands.

Many children found it difficult to adapt to their new lives in Canada. Not only was the climate more extreme than what they had known in Britain, but often so was the farm work. Many of the children had no experience or skills in the tasks they were required to complete, having grown up in British cities. It was not uncommon for employers to complain about their placement’s capabilities. If the children were not working to a satisfactory level, or if their labour was no longer needed, they would be returned to the central receiving agency.

Consequently, Home Children had childhoods filled with uncertainty, made harder by living in an unknown country away from all family and friends. Worse still was the psychological and physical abuse some faced at the hands of frustrated or prejudiced employers.

In Britain, impoverished parents were described as immoral in order to justify the taking of their children. However, records show that more children entered British children’s homes due to economic reasons than issues connected to morality. Many children were brought in because their parents or families could no longer financially support them. This misconception about the children and their families affected how they were received and treated in the program.

While some of the children were welcomed into their Canadian homes with open arms, an estimated two-thirds of the children faced some sort of mistreatment during their placements, often because of this class-based prejudice.

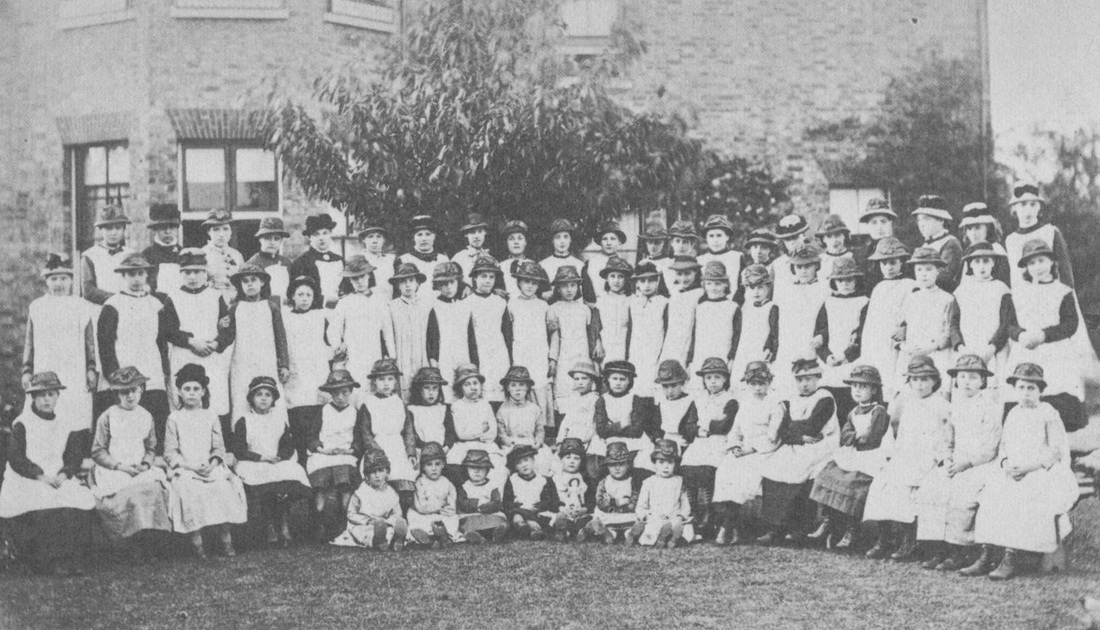

A group of Barnardo children arriving in Toronto, Ontario. September, 1921. Courtesy of Home Children Canada.

The abuses did not cease with the conclusion of child migration; they persisted, leaving a lasting impact on the lives of the Home Children. Not only did they endure physical and emotional mistreatment, but they were also subjected to societal prejudice.

Lori Oschefski, President of Home Children Canada, November 27, 2023

Controversy & Mistreatment

Organizations such as Barnardo’s faced criticism for a lack of supervision during child placements, proving to be fatal for some Home Children.

Although not common, mistreatment resulted in the death of at least one Home Child. In November 1895, George Green, a 15-year-old boy who passed through Barnardo’s Toronto home, was found dead at his placement in Owen Sound. A post-mortem examination found that George was covered in bruises and cuts, had frost-bitten feet, and was suffering from infection and malnutrition.

Having only lived on the farm for five months, George faced intense neglect at the hands of his employer Miss Helen R. Findlay. Findlay claimed she kept the boy well, and that he was responsible for his injuries mostly through clumsiness, calling the boy “slow.” However, during the court proceedings in which Findlay was charged with the boy’s murder, witnesses came forward to assert that Findlay had physically and verbally abused George. Despite the testimonials, the jury was unable to come to a verdict and Findlay was freed.

While George’s story is an extreme case, several accounts describe mistreatment that resulted in death, runaways, or suicide for Home Children. Unfortunately, most agencies, Barnardo’s included, could not properly supervise the Home Children placements to ensure the children’s safety or well-being. Agencies seldom had the resources to check the thousands of children spread throughout the Canadian countryside. In situations where mistreatment was identified, or when a child became sick or an employer wanted to discharge their ward, children would find themselves back in Toronto only to await their next placement.

A group of Barnardo children at a landing dock. Saint John, New Brunswick. Circa 1920. Image by Isaac Erb. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

The significance of Toronto in the Home Children narrative is reflected not only in the sheer numbers it accommodated but also in the lasting impact it had on the lives of those who found a new home in the city.

Lori Oschefski, President of Home Children Canada, November 27, 2023

Ending the Program

Many survivors of the Home Children program chose to keep silent about their experiences after the program ended in Canada.

The mistreatment that Home Children faced left a lasting impact. The program officially ended in Canada in 1939 with the outbreak of the Second World War, although British Columbia continued to receive children from Britain until 1948. With the closure of the child migration scheme, Barnardo’s has since pivoted to supporting displaced children, victims of abuse, and adoptions and fostering.

In their adult lives, many survivors of the Home Children program chose to keep silent about their experiences. Although it is estimated that descendants of Home Children make up 10 per cent of Canada’s current population (approximately four million people), many Canadians are unaware of their connection to the Home Children.

Although this history is relatively unknown, since the early 2000s, there has been a growing interest in understanding and preserving the history of the Home Children. Small, not-for-profit organizations, mostly created and run by descendants, have emerged all over Canada with the hopes of preserving this shared history. These organizations often highlight the impact the Home Children had on Canadian history, such as their contributions during the First and Second World Wars. Genealogical resources are often also provided, in hopes of connecting Canadians with their family’s heritage.

Barnardo’s headquarters on Peter Street. Toronto, Ontario. Circa 1913. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

Remembering the Home Children

Although this history remains largely unknown by the public, people are working to recognize the contributions made by the Home Children in Canada.

One such group, Home Children Canada, has had a hand in commemorating the Home Children in Toronto. On October 2, 2017 a memorial to the Home Children was unveiled in Etobicoke at Park Lawn Cemetery. Here, in two grave plots still owned by Barnardo’s, lie the remains of 75 Home Children.

Of the 75 children buried there, 17 were infants born to girls living in Barnardo’s homes; others died from illnesses such as tuberculosis or septicemia. Through archival records, death certificates, and cemetery plot cards, Home Children Canada was able to identify all of the children in the plots. The memorial stands not only to remember the children buried there but also as a symbol of all the Home Children who were brought to Canada through the emigration scheme.

Park Lawn Cemetary Monument erected by Home Children Canada. Etobicoke, Ontario. June 15, 2019. Image by Greg Stacey. Courtesy of British Home Children Canada.

Sponsor

References and Further Resources

Primary Sources:

Barnardo, Thomas John, “Something attempted, something done!”. London: J.F. Shaw, 1889.

The Toronto World, “Dr. Thos. Barnardo is Dead His Life Spent for Others,” September 21, 1905.

Secondary Sources:

Bagnell, Kenneth, The Little Immigrants: The Orphans Who Came to Canada. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1982.

British Home Children in Canada

Corbett, Gail H. Barnardo Children in Canada. Peterborough, Ontario: Woodland Publishing, 1981.

Englander, David. Poverty and Poor Law Reform in 19th Century Britain: From Chadwick to Booth 1834-1914. New York: Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1998.

Kershaw, Roger and Janet Sacks. New Lives for Old. Surrey: The National Archives, 2008.

Mok, Tanya. “This is why Park Lawn Cemetery in Toronto is home to two mass graves”, blogTO. November 12, 2023.

Oschefski, Lori. Home Children Canada, personal correspondence. [email protected]

Parr, Joy. Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to Canada, 1869-1924. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994.

Rose, Michael E. “Settlement, Removal and the New Poor Law”, in The New Poor Law in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Derek Fraser. London and Basingstoke: The Macmillan Press Ltd., 1976, 25-44.